Sustainability is now a board-level issue, and companies are under intense pressure to ensure their supply chains are environmentally and ethically responsible. Motivation may come from internal business, consumers, government, shareholders – or all of them. There are goals, commitments, deadlines and boardroom pressure to walk the talk.

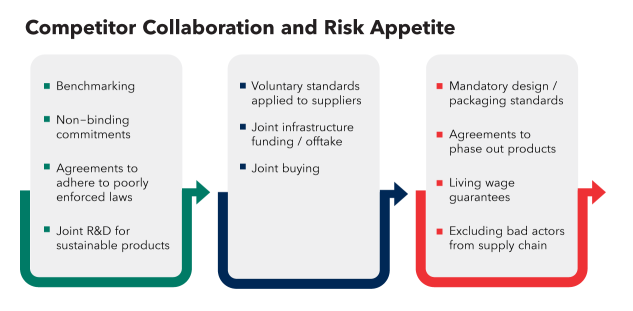

In some markets, companies pursue sustainability goals on their own in order to provide consumers with products they want and profit from them, but companies may not be able to drive change alone. A joint or sectoral initiative can sometimes achieve changes of a scale that cannot be achieved commercially by one company alone. But the prospect of rivals cooperating could raise questions about other antitrust laws in the United States and around the world.

Regulators cast a wide legal net because laws often focus on where an arrangement may have effects, rather than simply on where the parties are located. It is not always clear how national antitrust laws will treat sustainable collaborations that can increase costs and reduce choice.

The result is a complex and potentially risky legal environment for companies looking to take decisive action to achieve their goals and lead in their industry. So how should companies respond?

unacceptable cartel

U.S. lawmakers and antitrust enforcers have sent strong signals that they will not tolerate cartels under the guise of sustainable development agreements. Companies can be fined and sued and publicly accused of greenwashing – which takes time and resources to defend in court and before the public.

FTC Chairman Lina Khan responded to a question at a Senate hearing, claiming that there is no environmental, social and governance exemption from antitrust law.

Earlier this year, a coalition of 19 state attorneys general sent a letter to a major investment firm expressing concerns about “coordinating with other financial institutions to implement net zero raises antitrust concerns.”

In practice, cooperation may not actually be intended to limit competition. Sustainability managers or technologists may run projects (under pressure) but have little knowledge of antitrust rules because they are not considered to be undertaking risk-pricing functions.

Those implicated may believe that broader laudable environmental or social goals justify projects with competitors. Discussions on legitimate topics also risk straying into illegal territory, such as prices and the benefits of market stability. Employees may not be sensitive to the antitrust risks of long-running projects with scope creep.

collaboration allowed

Industry standards and benchmarks are a common way for companies to achieve more sustainable and ethical outcomes. Voluntary standards can have a positive impact on how workers are paid and the manufacturing methods that can be used, and can even play a role in making recycling more efficient.

There are clear benefits to standards, and many do not raise antitrust concerns. However, companies should ensure that standards are developed in a way that does not harm or exclude (i.e. resist) others.

Companies may also need to share information when developing voluntary standards, verifying compliance, or participating in benchmarking. They can be brought into compliance by using non-disclosure agreements, cleaning teams or third parties to aggregate the volume data provided.

If enough companies are involved that no single contributor can reverse engineer their competitor’s information, then there will be no antitrust concerns.

end call

The challenge for firms and consultants is to decide what to do with projects on the right side of the continuum, which may require a cost/benefit analysis.

This is difficult because qualitative benefits are harder to quantify or may be more uncertain, eg. Because they only appear in the long run. Unfortunately, companies may conclude that short-term antitrust scrutiny is more certain than environmental and commercial interests.

There are no easy answers to this type of project and the legal assessment is always based on facts and jurisdiction. We recommend the following tips to reduce risk:

- Make sure those responsible for corporate sustainability programs seek antitrust counsel.

- Consider auditing the ESG activities of the group to ensure in-house counsel understands what is happening and why any joint project has to be undertaken: does the initiative mean it cannot be achieved alone in terms of risks and costs?

- Ensure that projects retain as much room for competition as possible, for example by encouraging individuals to determine for themselves how to reach and exceed any jointly set goals. Identify and quantify the program’s benefits, who will benefit, and when.

Train all employees who come into contact with competitors on how to conduct meetings, using a dos and don’ts sheet tailored to the project. Make sure each initiative has a compliance program that covers information exchange safeguards and the use of third parties to avoid sharing sensitive information. Have corporate counsel regularly check for scope creep, and consider bringing outside counsel to important meetings to ensure the conversation stays on track.

Also, consider the pros and cons of approaching government agencies and/or antitrust agencies about the planned project, which may be a good option where a major investment is planned.

Don’t shy away from ESG

Antitrust law, or perceptions of it, could hinder legitimate projects focused on more sustainable supply chains, frustrating not only businesses but also antitrust agencies. However, with careful planning, companies can take steps to ensure that antitrust laws do not unnecessarily impede legitimate ESG objectives.

This article does not necessarily reflect the views of Bloomberg Industries plc, the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Writing for Us: A Guide for Authors

author information

Jeffrey Martino is a partner in Baker McKenzie’s global antitrust and competition practice and co-leads the firm’s global cartel task force.He represents multinational corporations and their boards and executives in high-stakes criminal and civil investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice and other agencies.

grant murray is lead knowledge counsel in Baker McKenzie’s London-based global antitrust and competition practice group. He leads a team of antitrust knowledge lawyers and is responsible for the training needs of a practicing team of more than 300 competition lawyers in more than 40 countries.